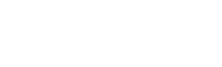

UK productivity has been flat since the banking crisis and is now 14 per cent below the level that would have been achieved if pre-crisis trends had continued.

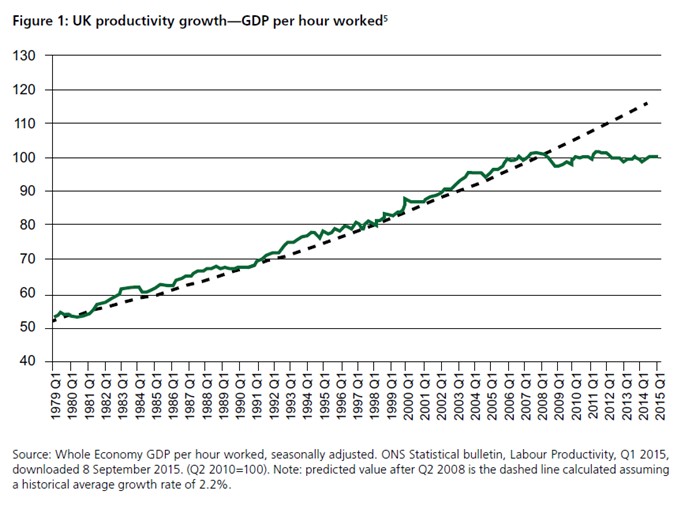

Addressing this, it is hard to disagree with the government’s overall strategic framework for raising productivity. It covers 15 policy areas from long term investment in competitiveness, skills, infrastructure and knowledge to the creation of a dynamic economy with fair and flexible markets, world leading financial services, openness and resurgent cities.

However, without converting these strategic imperatives into successfully executable actions, this is all “motherhood and apple pie” as our American friends would say.

The House of Commons Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) select committee has recently reported on the Government’s Productivity ‘Plan’.

The select committee reported that the Government is right to be concerned by the lack of productivity growth in the United Kingdom and endorsed the analysis of the problem, but it questioned “whether the document has sufficient focus and clear, measurable objectives to be called a ‘plan’. This broad and expansive document represents more of an assortment of largely existing policies collected together in one place than a new plan for ambitious productivity growth…”

Indeed the report quoted businesses who stated that the government’s productivity plan is “too vague…to be practical”

The committee recommended that the Government produce a clear supplementary document outlining the proposed implementation and measure of success of each policy in the Productivity Plan, regularly updated with progress against key milestones and dates. “Of the 16 chapters of policy areas in the Plan, very few have usable measures of performance. It is only once the Government publishes quantifiable metrics of success and a roadmap to implementation of the policies contained within the Plan, will Parliament be able to hold Ministers to account.” An obvious case of what gets measured gets done…

The BIS committee also referred to a recent Science and Technology (S&T) committee report on the Science Budget. Its report noted that in 2002 the European Council “adopted a target of spending three per cent (3%) of GDP on public and private sector R&D”. It further stated that publicly funded R&D creates a strong ‘multiplier effect’ and ‘crowds-in’ private sector, charitable and inward investment, stimulating around 30 per cent more self-investment from industry. The S&T committee reported that the United Kingdom’s “level of public and private R&D investment has been internationally low and falling”, stating that in 2012, it only invested 1.72% of GDP into R&D. The UK is clearly underinvesting in R&D compared to its peers.

Despite this, the BIS committee identified measures in the 2015 Spending Review that do not promote productivity. Specifically it was concerned to note that the Government has announced that £165 million per year that was given to businesses as an R&D grant to promote investment and crowding-in, will be converted to loans.

The committee naturally found it difficult to accept that many businesses prefer to pay back a loan, rather than receive a grant and were concerned that this would discourage businesses from taking the risk to invest in R&D. The committee went on to recommend that the Government should explain how this will help boost R&D investment and provide specific evidence of the rationale behind this shift in policy.

The committee heard anecdotal testimony of the Minister that businesses she had spoken to had stated that they would prefer to take out a loan (that they have to pay back) rather than be given a grant (that they do not). “We struggle to accept that the majority of rational businesses in the UK share that view.”

Indeed, under what circumstances would anyone not prefer a grant to a loan…? (Too complex to apply for and too much bureaucracy perhaps?)

The BIS committee went on to specifically recommend that the Government provides:

- The clear rationale for moving R&D grants to loans.

- The modelling done with a clear statement that the Government expects this to result in more/same/less private investment in R&D.

- What proportion of current public investment in R&D it will convert to R&D loans from previous R&D grants.

- What proportion of R&D loans it expects to be repaid (i.e. the equivalent RAB charge in relation to student loans).

Until these issues are answered, The UK’s clear underinvestment in R&D compared to its peers and the government’s misunderstanding of what support SMEs need look set to stay…

The committee also noted that another recent report, produced jointly by Goldman Sachs and the British Business Bank found that small businesses should be encouraged to grow, as there was some hesitancy in ambition which “served as a warning that policies should avoid dampening that ambition further.” The committee further noted that a 2015 Report published by Octopus Investments which stated that “high growth small businesses have common needs: finance, talent and connectivity.” The Government should support all of these.

It is important, that the UK has an economy where successful small businesses can scale-up into successful larger businesses. “Only by doing so will the economy experience sustainable GDP growth, employment and higher exports. Helping small businesses to improve their productivity will benefit the whole economy.”

So, improved productivity, investment in R&D and support for SMEs all go hand in hand. The select committee’s conclusions suggest that the government needs to take some lessons in how to execute strategy successfully and grant v debt financing options; something, as an ex criminal barrister, the small business czar should surely understand…

- The Governments Productivity Plan – BIS Committee Report

- Real Business – vague productivity plan

- Guardian - UK's productivity plan is ‘vague collection of existing policies’

- CIPD - MPs deride government's 'unclear' plans to boost UK workforce productivity

- FT - Productivity: It's a drag (registration required)